Mr. Trump’s draft budget blueprint eliminates many environmental, cultural, human services, and science based programs. I will address two of the programs with which I have direct experience – the Institute of Museum and Library Services and the Corporation for National and Community Service.

Mr. Trump’s draft budget blueprint eliminates many environmental, cultural, human services, and science based programs. I will address two of the programs with which I have direct experience – the Institute of Museum and Library Services and the Corporation for National and Community Service.

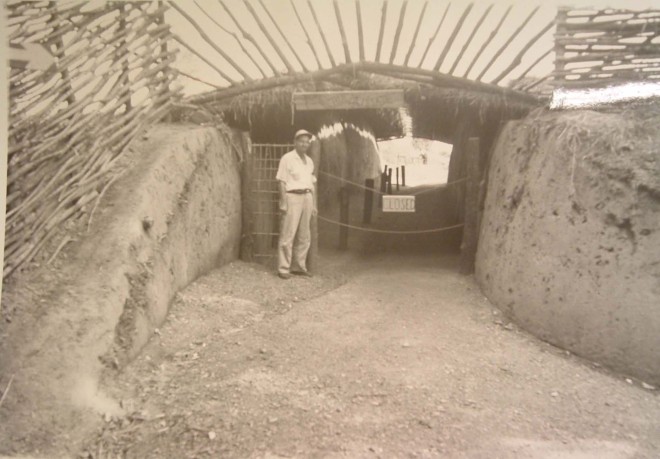

In 2007 I was hired as the Director of the C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa, a small prehistoric venue in Southwest Memphis, Tennessee. The Museum had fallen on “hard times” as it were. In essence, my assigned task was to rejuvenate the place or the Museum would likely be shut down. Over my nine-year tenure, we eliminated the Museum’s operating deficit and made up past deficits. Also, the annual attendance doubled. The C.H. Nash Museum began to play a critical role as a cultural heritage venue in Southwest Memphis, became an integral educational resource for the University of Memphis, and a national model for co-creating with a local community whose tax dollars supported the Museum. Both the IMLS and CNCS were critical to that process. Simply put, the successes of the Museum would not have occurred without the support of these two institutions.

The Institute of Museum and Library Services

The C.H. Nash Museum was able to take advantage of several services offered by the IMLS:

- Connecting to Collections, of which IMLS is a founding partner, awarded the C.H. Nash Museum a set of books valued at over $1500.00 to help us become better informed on the best practices necessary for curating our 50 years worth of collections, many of which had not been properly cared for in decades. The book award is no longer offered because now the IMLS provides that scope of resources online, a more cost-effective means for distributing the information. Connecting to Collections also hosts regular webinars on a diverse range of issues. All Connecting to Collections services are provided free to museums. This service is absolutely critical to small museums throughout the U.S. that are operated by either volunteer or small staffs. Specifically, small museums such as Chucalissa do not have access to funds to hire consultants with the expertise needed to conserve, preserve, and present the cultural heritage they curate.

- The IMLS’s Museum Assessment Program (MAP) proved absolutely critical to our Museum’s turn around. The C.H. Nash Museum was founded in 1956, but there was limited attention paid to its maintenance or upgrades over the years. For example, in 2007, no museum exhibit was upgraded for nearly 30 years and many of the collections were not properly curated. The MAP program consisted of a period of intensive self-study followed by a peer review from a nationally recognized museum professional matched specifically to our institutional needs. The reviewer provided a series of recommendations grouped by duration (short-term, medium-term, and long-term) and cost (no expense, modest expense, or major expense). Of importance to our governing authority, the peer reviewer’s recommendations came with the credibility of the nationally recognized leaders in the field – IMLS and the American Alliance of Museums. The recommendations provided leverage for our Museum and were integral to our strategic plan developments. Our Museum simply did not have the 15-20 thousand dollars necessary to hire a private consultant to perform these services. Our total cost for the program was $400.00.

As the recently retired Director of a small museum along with my years of service on small museum boards and professional organizations, without question, the small institution, often in a rural location will be most directly and negatively affected in eliminating the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Corporation for National and Community Service – AmeriCorps

To the extent IMLS allowed us to strategically reorient our Museum, AmeriCorps allowed us to carry out those changes. NCCC AmeriCorps is the legacy of the 1930s-era Civilian Conservation Corps and is composed of youth between the ages of 18-25 who give one year of community service. At the C.H. Nash Museum, we hosted six AmeriCorps teams over a four-year period. These teams were integral to our ability to serve and engage with our neighboring community. We devised a unique partnership where each 8-week AmeriCorps team spent 1/3 of their rotation working on each of three separate components: the C.H. Nash Museum, the surrounding community, and the T.O. Fuller State Park as follows:

- Teams working in the surrounding community focused on minor to moderate repair and landscaping work on the homes of elderly veterans in the 95% African-American working class community that surrounds the C.H. Nash Museum.¹ In addition, team members served as mentors to neighborhood youth in this underserved community and leveraged corporate support for their projects. ²

- Teams working at the C.H. Nash Museum developed skills and performed structural improvements to the site including creating gardens, lab exhibits, rain shelters, refurbished onsite housing and much more.

- Teams working at the T.O. Fuller State Park completed maintenance projects such as refurbishment of picnic shelters and trail maintenance. The T.O. Fuller State Park is particularly significant in Memphis history as the only such recreation facility available for the African-American community during the era of Jim Crow segregation.

Both IMLS and AmeriCorps teams led to building relationships and leveraging assets to bring additional resources into play that would not have been otherwise available. For example:

- The IMLS Connecting to Collections resources allowed Museum staff to generate the types of data based proposals to generate additional economic support from the governing authority.

- Similarly, the IMLS MAP program help to demonstrate the fiduciary responsibility of the governing authority to the collections and infrastructure of the Museum, leading to additional economic support in the form of staff and material support.

- The AmeriCorps Teams strengthened community connections that today allow the C.H. Nash Museum to host the community’s Annual Veterans Day event, the annual Black History Month Celebration, provide space and resources for a community garden, provide internships for local high school students, to name just a few.

In summary, elimination of the IMLS and the CNCS will also cut the potential for projects such as those noted above at the C.H. Nash Museum. In 2012, the House of Representatives passed H.Con.Res.112 that called for eliminating the National Endowments for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts noting that “The activities and content funded by these agencies . . . are generally enjoyed by people of higher income levels, making them a wealth transfer from poorer to wealthier citizens.” My examples demonstrate such statements are erroneous. In fact, as demonstrated in the case of the C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa, the elimination of IMLS and CNCS will directly impact the small and particularly rural museums that serve as the cultural heritage hub for their communities and will not put “America first” an alleged goal of Mr. Trump’s budget.

An immediate and strong response must be sent to all legislators to counter proposals to eliminate these and similar programs that truly do put all of America first.

¹References for this work include the following: Making African American History Relevant through Co-Creation and Community Service Learning by Robert P. Connolly and Ana Rea; The C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa: Community Engagement at an Archaeological Site by Robert P. Connolly, Samantha Gibbs, and Mallory Bader; AmeriCorps Delta 5 – Unparalleled Community Service by Robert P. Connolly; AmeriCorps, Archaeology and Service by Robert P. Connolly; AmeriCorps Archaeology and Museums by Robert P. Connolly.

² AmeriCorps NCCC: The Best of the Millennial Generation by Ana Rea.