As I noted in my last post, for the past few years, half of the final exam in my Museum Practices graduate seminar in the Museum Studies Program at the University of Memphis consists of responding to the following:

Put yourself in the position of John or Josephine Q. Public. In the current economic chaos, the bank is foreclosing on their home, they have lost their jobs, and the city just reduced their public services. In referring to the National Endowment for the Arts and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the House Budget Committee recently argued that “The activities and content funded by these agencies…are generally enjoyed by people of higher income levels, making them a wealth transfer from poorer to wealthier citizens.” Isn’t your research or the position you aspire to a museum professional just another example of this wealth transfer? What do John and Josephine Q. Public get for their tax dollars that fund your research/position?

Another excellent essay was written by Brooke Garcia a graduate student in the Institute of Egyptian Art and Archaeology at the University of Memphis. Brooke is also enrolled in the Museum Studies Graduate Certificate Program and is a Graduate Assistant at the C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa. Drawing on her own experience at Chucalissa and the Third Place concept she provides an excellent response to the essay challenge.

Another excellent essay was written by Brooke Garcia a graduate student in the Institute of Egyptian Art and Archaeology at the University of Memphis. Brooke is also enrolled in the Museum Studies Graduate Certificate Program and is a Graduate Assistant at the C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa. Drawing on her own experience at Chucalissa and the Third Place concept she provides an excellent response to the essay challenge.

What the Publics Get From Museums

by Brooke Garcia

I would venture to generalize that a good portion of people still view museums as the ivory tower[1], a repository of artifacts only accessible to the wealthy elite. However, more museums today recognize this stereotype and are taking steps to change this misguided, outdated perception. At least in theory, museums reflect the needs of their community, and as discussed previously, if they do not change to reflect these needs, museums will cease to exist. One of these needs is to be affordable in difficult economic times and provide more than just exhibits. Museums need to be an experience, and despite the hardships John and Josephine Q. Public have endured, they should still be able to participate in museums. It is their space, a third space, for the community to utilize, learn from, and enjoy.

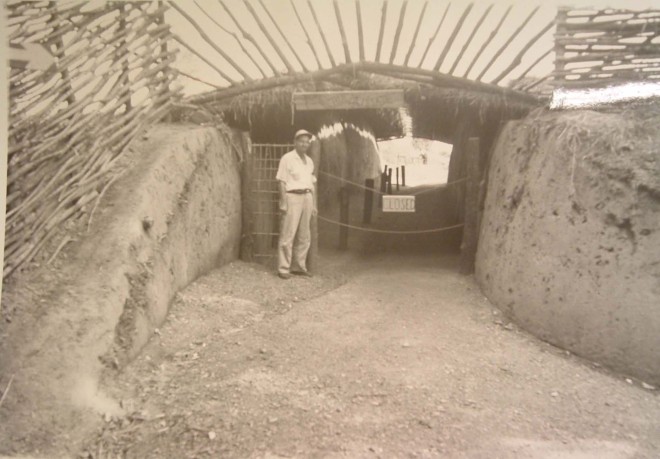

For the sake of this paper, John and Josephine Q. Public live in Southwest Memphis, and their local museum is the C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa. As a graduate assistant at the C.H. Nash Museum and a student at the University of Memphis, their tax dollars help fund my position. But what do they receive in return? The C.H. Nash Museum strives to be transparent, and their educational and economic impact statements tell Mr. and Mrs. Public what their taxes pay for. Their taxes fund staff, who in turn help create new exhibits and education resources, such as the African-American Cultural Heritage in Southwest Memphis exhibit, Medicinal plant sanctuary, resertification of the arboretum, and the Hands-on archaeology lab.[2] Their children, Joseph and Johna Public, visit the museum with their elementary school and benefit directly from the graduate assistant and staff-led tours, education programs, and crafts, which include Mystery Box, Native American Music, Pre-history to Trail of Tears, Talking Sticks, Simple Beading, and many more.[3] As a family and for regular admission price, the Publics can participate in Family Day programing on every Saturday plus some weekdays in the summer.

But how can they benefit more? Given their economic hardships, even paying regular admission prices could be difficult for their entire family. Perhaps the C.H. Nash Museum needs to consider offering free days to locals or two-for-one ticket deals once a month. I also think providing free, open to the public, academic lectures about the prehistoric and historic Chucalissa site would benefit the museum greatly. These lectures could also be a platform to display artifacts usually not on view. The Publics could enjoy these lectures with their children without worrying about their hardships and learn even more about the site or other special topics than even a regular visitor would. This situation exemplifies what we as researchers and museum professionals can do for the public that shows museums are not a wealth transfer, they are a place to exchange information and a third space for the community.

As defined by the Center for the Future of Museums blog post “Experience Design & the Future of Third Place”, the third space includes spaces “not home, not work public-private gathering places” for the community.[4] The third space is “for people to have a shared experience, based on shared interests and aspirations [and] open to anyone regardless of social or economic characteristics such as race, gender, class, religion, or national origin.”[5] Furthermore, these spaces are “often an actual physical space, but can be a virtual space, easily accessible, and free or inexpensive.”[6] Examples of third spaces include: coffee shops like Starbucks, public parks, malls, chat rooms, fairs, and even museums. In exchange for their tax dollars, the Publics have access to government-funded third spaces like museums and parks. However, what separates museums from these other third spaces? Museums are a place for learning and entertainment. Instead of coming away with a new dress or a Frappuccino, museums visitors (hopefully) take away new information, or at the very least, a new experience. At the C.H. Nash Museum, the Publics can learn about the prehistoric Native American site, but also the past and contemporary history of their community. And they can also participate in community events, such as the local Black History Month celebration.[7] Even with hardships, they can take advantage of their museum as a third space.

Museums today are not a space just for the wealthy. More and more museums strive to provide a place for their community to gather and learn. No longer are museums just about artifacts, but now, in my opinion, their true mission should focus on education, in all forms for all ages. Education through exhibits, programs, activities, crafts, etc.; in other words, museums are a third space, focused on passing on new information to their visitors and providing for the needs of their community, whether that includes Richie Rich or John and Josephine Q. Public.

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Ivory Tower,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation Inc., last modified December 10, 2014, accessed December 10, 2014. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivory_tower

[2] C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa, Educational Impact Statement, 1, accessed December 10, 2014. http://www.memphis.edu/chucalissa/pdfs/chuceduimpact.pdf

[3] Some of these mentioned in C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa, Economic Impact Statement, 1, accessed December 10, 2014. http://www.memphis.edu/chucalissa/pdfs/chuceconimpact.pdf

[4] “Experience Design & the Future of Third Place,” Center for the Future of Museums Blog, April 3, 2012, accessed December 10, 2014. http://futureofmuseums.blogspot.com/2012/04/experience-design-future-of-third-place.html

[5] California Association of Museums, Foresight Research Report: Museums as Third Place, Report for Leaders of the Future: Museum Professionals Developing Strategic Foresight (2012), 5. http://art.ucsc.edu/sites/default/files/CAMLF_Third_Place_Baseline_Final.pdf

[6] Ibid.

[7] Chucalissa, Economic Impact Statement, 1.